So my thesis is coming up. Once I finish these assignments, I’ll probably be knee deep in that 🙂 In an attempt to keep the ‘flow’ of writing going, I’m going to start blogging a bit more. I apologize, in advance, if my blogs are boring and not as activist as they have been…but it’s all a work in progress. Here’s my assignment, which I just emailed in and hope I don’t get into trouble for publishing on a public space 🙂

2018/MAEN/03

ENG 6206

DIGITAL CULTURES

ENGLISH DEPARTMENT

UNIVERSITY OF COLOMBO

This paper seeks to examine posts from three Instagram accounts in order to explore the use of feminism on this digital platform. These Instagram accounts are not personal accounts, but instead represent movements and institutions which have political alignments in terms of their feminist goals. The paper will use Donna Haraway’s “Cyborg Manifesto” and Kaye Mitchell’s “Bodies that Matter” as primary texts, in order to examine how ‘activist’ these accounts and their posts are, and how layers of meaning can be divulged through this digital and visual medium.

Although initially a platform exclusively for iPhone users, Instagram has now become one of the most popular social media platforms today. With the advent of Web 2.0, Instagram has superseded other social media platforms and is one of the most accessible and visual mediums for expression on a digital medium.

Compared to Twitter, which is largely text based, Instagram is more visual and appealing. In an interesting study, Hu, Manikoda and Kambhampati sought to categorize the content of Instagram photos and identify, broadly, user types. The premise of their study was to identify “(how) having a deep understanding of Instagram is important because it will help us gain deep insights about social, cultural and environmental issues about people’s activities (through the lens of their photos)” (595). Continuing on the premise that Instagram images reflect cultural issues, is that of feminism and activism. Instagram has evolved into a space where activism reigns. With the advent of the #MeToo movement, TimesUp and the Women’s March, the platform has seen an explosion of various accounts aimed at buoying feminist sentiments, empowering women and motivating social movement.

As a relatively new medium for activism in today’s post-feminist age, Instagram users and accounts are still very broad in their approach to activism and instigation. The medium allows for multimodality, which is a feature many users make the most of. Posts, however can range from screen shots, to historic images of notable activists, or inspirational quotations. Within a loose framework of cyberfeminism and activism on Web 2.0, an analysis of such accounts and posts will seek to engage with varied means of carrying out activism online – which is where the feminist movement has progressed to, from the streets.

Sheldon and Bryant, in 2015, examine the motives for users of Instagram; they quote McQuail, Blumler and Brown (who in 1972 examined the gratification gained from using “all types of media”), “the main (types of gratification) include: diversion (escape from problems; emotional release), personal relationship (social utility of information in conversation; substitute of the media for companionship), personal identity (value reinforcement; self-understanding), and surveillance” (90). Sheldon and Bryant conclude that what is posited on Instagram is formulated around a person’s identity and not his/her relational identity (90). Additionally while there are many social and/or psychological predictors that drive Instagrammers, according to Sheldon and Bryant gender is the best predictor; women are most likely to be more active on this platform (90-95). In 2018, Internet statistic websites such as Omnicore, hootsuite and brandwatch prove that more than 60% of Instagram users are female. Thereby it can be concluded that this social media platform is a fertile ground for activism and empowerment.

What is Cyberfeminism?

The third wave of feminism is absent on the streets. As mentioned previously, I believe it has moved its activism onto the digital sphere. This shift is integral to the concept of ‘Feminist Media’. Linda Steiner defines Feminist Media as:

“media that consistently advocate expansive political, social, and cultural roles for women and expose gender oppression (interstructured with oppression by sexual orientation, class, “race,” ethnicity, and religion, or other bases of invidious distinction). Sympathizers and advocates can thereby redefine news, share information unavailable in mainstream media, and, just as importantly, nurture a feminist community” (1) (emphasis mine).

In light of this definition, posting on Instagram can definitely be considered as Feminist Media.

Susanna Paasonen takes the term to a new level in delineating the concept and breaking down its barriers and boundaries. She writes (that) “anyone can, and everyone should invent her own cyberfeminism” (336).

The term ‘Cyberfeminism’ was coined by British cultural theorist Sadie Plant who used the feminist art movement, VNS Matrix’s line “the clitoris is a direct line to the matrix” as a foundation upon which she built her own manifesto (Paasonen, 338). Plant’s narrative “ties women and machines together as tools (and others) of masculine culture and promises complicated and intertwining webs that will eventually overturn the phallogocentric hegemony. According to Plant, the digitalization of culture equals its feminisation while the rise of intelligent machines parallels female emancipation” (Paasonen, 338) (emphasis mine).

A seminal work in this field is Donna Haraway’s ‘Cyborg Manifesto’, where Haraway posits the cyborg as a “creature in a post gender world” (8), who is also “a kind of disassembled and reassembled, postmodern collective and personal self. This is the self feminists must code” (33). Haraway encourages a ‘reading’ of power structures within these digital networks and advocates that women learn to bypass these boundaries; “to read these webs of power and social life, we might learn new couplings, new coalitions” (46). Haraway’s manifesto, to me, is a call to arms – for women to ‘own’ the new digitized sphere and make it theirs.

A majority of Instagram users are women who utilise this space to “redefine news, share information unavailable in mainstream media…(and) nurture a feminist community” (Steiner, 1). Moreover each of these women “invent(s) her own cyberfeminism” (Paasonen, 336) on this platform, and works towards the feminization of digital culture within Instagram (Paasonen, 338), and deconstructs these power structures (Haraway, 46) – it is evident that Instagram can be considered a hotbed for cyberfeminism and activism.

rebelgirlsbook

This Instagram account belongs to the popular children’s book ‘Goodnight Stories for Rebel Girls’. I follow the account because I have the First Volume, and I love the concept behind the re-portrayal of stories about real women. The account is not only for publicity purposes, but also for images and text which can be empowering. The book itself is feminist in content, providing alternate stories to children aged six upwards. The illustrations are beautiful and the presentation is appealing to both adults and kids. Both my 5 year old daughter and 7 year old son are enthralled by many of the stories, and we’ve spent hours online researching some of these ‘real’ storybook characters – which is a novelty to them. I believe the account embodies cyberfeminism because of the array of content and socio-political issues it tackles. I’ve selected four posts to examine within the framework of cyberfeminism.

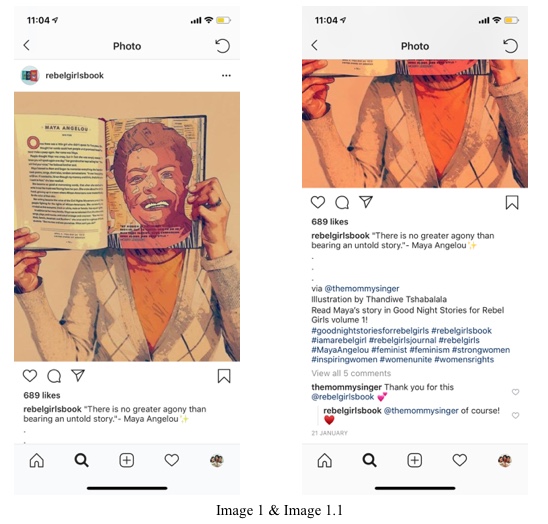

Image 1 is of Maya Angelou’s page in the ‘Goodnight Stories’ book. While I’m not sure who’s holding the book up, the illusion that Angelou is, is noteworthy and interesting. Additionally the image shows the constructed nature of the account’s primary purpose – which is as a marketing tool for the book and a method of awareness creation. What is more interesting is that the post is a re-post from another user, @themommysinger. This shows the far reaching effects of the book where it has inspired art by others which has been, in turn, digitized. The hashtags are also empowering in terms of the agenda of cyberfeminism.

Haraway notes that “writing is preeminently the technology of cyborgs…cyborg politics are the struggle for language” (57). To me, this image speaks volumes in terms of the context of writing – the book itself is a written form and embodies the tales of so many women who have been, and continue to be, role models for children. The sheer success of this written text is evident in the fact that its been translated into multiple languages and enjoys global best seller status. Yet this image appreciates the book, and while appreciating art and beauty also posits a sense of awareness about how an image can be both constructed and layered with meaning: what Maya Angelou represented as a person; what the storybook represents to children and progressive parents around the world; the shadows and colours of the image (it has been altered to mimic a painting); the use of the book plus the human hands that hold the book, and the anonymity that the book offers; the woman is obviously not young, suggested by her cardigan and Instagram handle (@themommysinger); the symbolic hiding behind the book to give herself Angelou’s face perhaps to immortalize her, and the hashtags which are integral to Instagram and allow access irrespective of digital platform. The struggle for language is evident the multiplicity of layers that were needed to create this meaning; there needed to be layers for the right meaning to be conveyed.

Image 2 is an original post by the Rebel Girls account as evidenced in the ‘RG’ logo at the bottom right corner. Again the image is layered with meaning and definitely advocates empowerment and can be considered cyber feminist. The protest, as a movement for change, is in keeping with the many recent protests by women around the US – and if you take a closer look at the hashtag #womensmarch, you’ll know this is in direct support of that movement. The sign that the central character is holding is also interesting because of the Cinderella tale. The book itself is a subversion of all fairytales. Ironically the book released a video called ‘Cinderfella’ on Youtube, which ended with the question “We wouldn’t read this to our sons. Why read it to our daughters?” (Rebel Girls, ‘If Cinderella were a guy’)

The protesters in the image are multi ethnic, evident by the varied shades of skin colour. They’re also dressed differently and in front of a pink sky. The subversion of the colour pink, which is associated with little girls and hyper-femininity, in the background of such an image is also noteworthy because it implies the ‘taking back’ of the colour pink as a colour of empowerment. Kaye Mitchell, in ‘Bodies that Matter’, discusses how the body is not “transcended in cyber space…but remains a factor that cannot be disregarded”. Within this context the bodies in the image, albeit as cartoons/illustrations, are powerful because they stand for different forms, shapes, sizes and colours of women who march and protest for a common goal. The image is also a subversion of power structures and hierachies; feminism and activism is for women of all shapes, colours, sizes and ethnicities. It is, as Haraway notes, the “(reading) of these webs of power and social life” and a “learning” of “new couplings” on this digital platform (46).

This image is interesting because Sara Erdmann had tweeted this in 2013 in response to high prolific rape cases that had occurred at that time. The tweet has (literally) switched mediums from a tweet, to a protest sign and then onto Instagram as an image. This is multimodality and diversity of information. Erdmann is not a celebrity nor a social media influencer, she had just randomly shared her thoughts via Twitter. Interestingly the Rebel Girls account has shared the post from another account, @whatshesaid. The proliferation of this information, and quotation is significant because it shows that this movement has exceeded the boundaries of Web 2.0, and come a full circle. The hashtags, again, are noteworthy in terms of empowerment and political movement.

Refinery29

Refinery29 is a media company focussed on young women (www.refinery29.com). Their Instagram page features images and articles primarily found on their website, spanning various categories such as fashion, makeup, beauty and lifestyle tips, while also touching on more serious issues such as body imaging, and mental and physical wellness.

Images 4 and 4.1 are of a plus size woman in a yoga pose. It is a regram, and the text that accompanies the image is detailed and very empowering. The photograph of this ‘body’ on social media can be considered through the thoughts Kaye Mitchell expresses in “Bodies That Matter”: that the body is “not transcended in cyber space” (111). Although Mitchell refers to the ‘gendering’ of these bodies, here it is the culture of bodies that need transcending. Given that Instagram is a social media platform, which allows for a certain freedom of expression (to an extent) it is able to question the norm and take steps to ‘transcend’ these limitations. Discrimination based on size is as serious an issue as sexism, and it is heartening for those who are built differently to have bodies like this, on a popular platform transcending the stereotype. The image calls out stereotypes and social stigma, and undermines it with the image while empowering those who are insecure about their bodies. Mitchell focuses on “Corporeal Feminism” where the body is examined in terms of how “the ‘matter’ of the body is socially and culturally constructed” (114). While this post is aware of the social and cultural constructions of bodies such as this, there is also an acceptance and its own ‘performance’ is normalized despite its lack of media representation and public acceptance.

This type of post is very common on the refinery29 Instagram page. Quotations from notable persons, with emphasis. This quotation is also in keeping with pillars of the feminist movement – to stand up against oppressive forces and not be silent. It is specifically targeted at the Holocaust Day of Remembrance, evident by the hashtag. Paasonen explores the varied meanings of cyberfeminism, which can be applied to the content of this post. She quotes Plant who’s stated that “the digitalization of culture equals its feminisation while the rise of intelligent machines parallels female emancipation” (338). In this post, and in many of the account’s posts, there is an attempt to broaden the selfie laden culture of Instagram and infuse it with a form of ‘feminisation’ – an increasing awareness of discrimination and a conscious shift towards empowerment, of not just women but other marginalized groups. Paasonen posits a third definition of cyberfeminism too, “cyberfeminism stands for analyses of the gendered user cultures of information and technologies and digital media, their emancipatory uses, as well as the social hierarchies and divisions involved in their production and ubiquitous presence” (340).

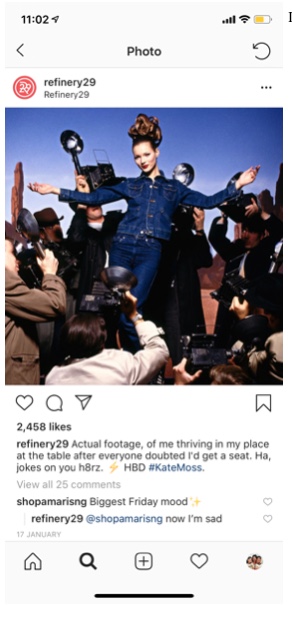

Image 6, also from Refinery29, was posted in honour of supermodel Kate Moss’ birthday. Paasonen’s third definition is once again evident through this image as well. There is Moss, and the representation of a supermodel and the implications of what her body is encoded with, confidently posing in (what appears to be) a desert. Her open arms and confident pose as she is bombarded by the paparazzi exudes confidence. The caption, “Actual footage, of me thriving in my place at the table after everyone doubted I’d get a seat. Ha, jokes on you h8rz”, rings true of Moss who’s personal life has been criticized in the media on many occasions in the past. The “social hierarchies and divisions” Paasonen mentions are evident because Moss is the only female in the image (340). Additionally none of the photographer’s faces are visible, hers is the only one – this is cyberfeminism because while we are made aware of the production of the hierarchies evident in the image, we value how emancipatory this image can be given Moss’ popularity in the past and at present today. The caption too is a subversion of the mediatisation of public figures because it implies that being successful is possible, no matter what field you’re in and no matter the criticism leveled at you. The final line of the caption, “Ha, jokes on you h8rz”, is notable because it is a reclaiming of power. Examining Moss’ posture and her attire, within the context of Refinery29’s content, Instagram and cyberfeminism is an examination and awareness of the multitude of ways in which the “matter of the body (can be) socially and culturally constructed” (Mitchell, 114). The body, as Butler states, “is a variable boundary” (114) and having exceeded socially constructed boundaries (as in Image 4) it is important to be aware of the “performance” of these bodies and what each performance represents within the sphere of this digital platform.

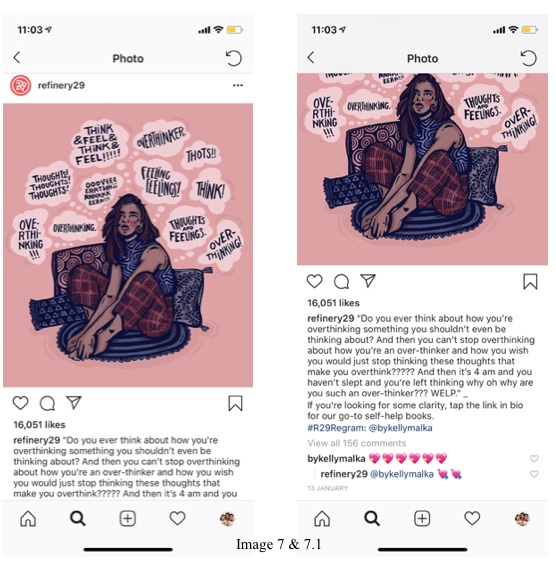

The next image touches on an important motif in Instagram culture: one of anxiety, self-awareness and self-care. That women are overthinkers is a stereotypical notion that women have been imbibed with for years; many women are asked to ‘calm down’, ‘take a chill pill’, ‘stop overreacting’ and ‘overthinking’ it – at this point I am reminded of Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s short story, ‘The Yellow Wallpaper’ in the context of female anxiety, hysteria and (perceived) insanity. As a result of these trends it has become easier to fit women into moulds of hysteria. While the image and its accompanying caption acknowledge the fact that yes, sometimes women can be over thinkers it also provides an outlet for those who have anxiety and are troubled by their thoughts – through the link and provision of self-help books. I feel images like these address serious wellness and mental health issues that women experience due to the multiplicity of roles we are supposed to play. Mitchell notes that the body can never transcend the boundaries of the Internet, that the assumption that the Internet takes away ‘gender’ is a baseless promise (111). An acknowledgement of these issues and solutions to overcome these very real problems is also a part of cyberfeminism; it is an active movement towards acceptance and resolution.

words_of_women

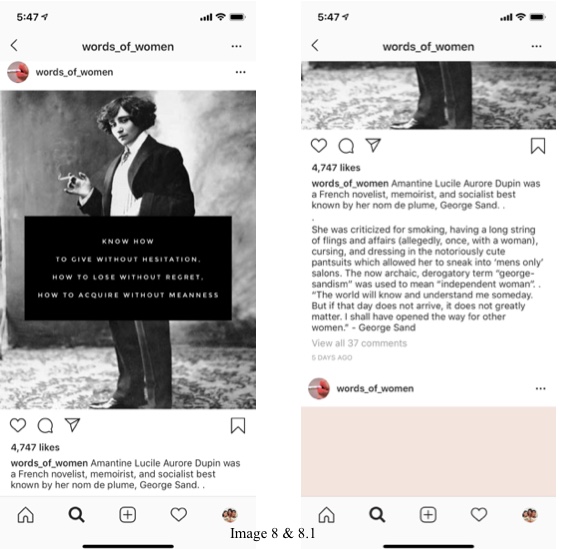

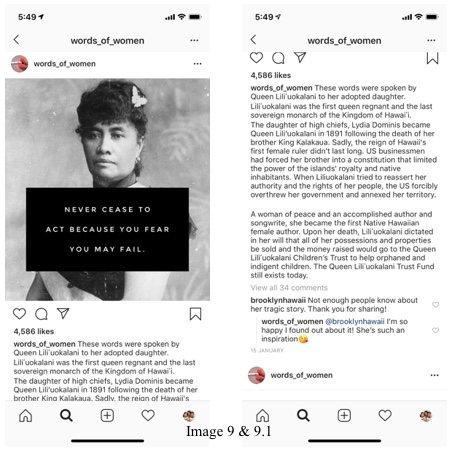

Lauren Martin, creator of the Instagram account words_of_women believes that “the nature of the Internet, especially Instagram, is, in many ways abusive towards women” (www.beyondtheinterview.com). She comments on the selfie-based and image-centric nature of the platform and admits that she has tried, through her account, to subvert this notion because the quotations she posts are strengthening, “they are these little pearls of wisdom from women who had come before me and done great things” (www.beyondtheinterview.com). The format of the account is simple: an image of a notable historical woman accompanied by a profound and/or empowering statement by each woman. Most often the quotation is accompanied by a caption detailing the life and works of each woman in the image.

Amantine Lucile Aurore Dupin’s subversion of the female body by dressing up in pantsuits, at a time when women did not wear them, is a statement. This post is important because of who George Sand was, what she represented and what her actions mean to us today, in retrospect. It is also a comment on the female body, and the notion that our bodies have been, and continue to be gendered. However awareness of women, such as Dupin, is empowering because it gives women hope that we can follow in the footsteps of George Sand and create revolutions for others to follow. Haraway notes that “communication technologies…are the crucial tools redrafting our bodies…these tools embody and enforce new social relations for women worldwide” (33). Given the impact George Sand made, in paving the way for the pantsuit and the ‘owning’ of the female pantsuit, it is safe to conjecture that she has paved the way for other women, and this post on Instagram (a platform that is predominantly used by women) will ensure that new social relations will be created in terms of continuing to “redraft” our bodies and what our bodies mean to us and to society at large.

Image 9 is of Queen Lili`uokalani, and as the caption suggests she was a woman of status and power. Political forces overthrowing her monarchy, didn’t stop her from working for the betterment of her people, and the fruits of her labour are still present. She represents a woman who truly lived by her words and never ceased to act because of fear of failure.

Martin’s account is definitely cyberfeminism; it is a reflection of Haraway’s notion that we must address the historical system that is dependent on “structured relations among people” and given that science and technology are newer sources of “power”, these sources should be accompanied by “fresh sources of analysis and political action” (37). This will enable social relations to propel socialist feminism towards “effective progressive politics” (Haraway, 37).

Conclusion

Instagram has become a fertile ground for cyberfeminism to thrive, in many forms and addressing many issues concerning the modern woman. Given the current climate of activism that has swept most of the Western world, it is likely that these fires will spread across the world through these digital channels. Mitchell comments on how the internet can be a space where a dialogue between a number of discourses can take place (125), whilst Haraway suggests a space where there’s “permeability” of boundaries so that “networking (can be) both a feminist practice and multinational corporate strategy” (45-46). I am of the opinion that Instagram has enabled such a space and there’s hope that cyberfeminsim will evolve with newer technologies and continue its activism in the digital sphere.

References

• Instagram by the Numbers (2019): Stats, Demographics & Fun Facts. 4 Jan. 2019, https://www.omnicoreagency.com/instagram-statistics/.

24+ Instagram Statistics That Matter to Marketers in 2019. https://blog.hootsuite.com/instagram-statistics/. Accessed 31 Jan. 2019.

“47 Incredible Instagram Statistics You Need to Know.” Brandwatch, https://www.brandwatch.com/blog/instagram-stats/. Accessed 31 Jan. 2019.

Haraway Donna J. ,Manifestly_haraway_——_a_cyborg_manifesto_science_technology_and_socialist-Feminism_in_the_….Pdf. https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/english/currentstudents/undergraduate/modules/fictionnownarrativemediaandtheoryinthe21stcentury/manifestly_haraway_—-_a_cyborg_manifesto_science_technology_and_socialist-feminism_in_the_….pdf. Accessed 4 Feb. 2019.

Hochman, Nadav. Visualizing Instagram: Tracing Cultural Visual Rhythms. p. 4.

Hu, Yuheng, et al. What We Instagram: A First Analysis of Instagram Photo Content and User Types. p. 4.

Mitchell, Kaye. “Bodies That Matter: Science Fiction, Technoculture, and the Gendered Body.” Science Fiction Studies, vol. 33, no. 1, Mar. 2006, pp. 109–28.

MP0306_Complete_Issue.Pdf. http://academinist.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/MP0306_Complete_Issue.pdf. Accessed 25 Jan. 2019.

Ng, Eve. “Structural Approaches to Feminist Social Media Strategies: Institutional Governance and a Social Media Toolbox.” Feminist Media Studies, vol. 15, no. 4, July 2015, pp. 718–22. Taylor and Francis+NEJM, doi:10.1080/14680777.2015.1053718.

Rebel Girls. If Cinderella Were a Guy… YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p4OyCNctKXg. Accessed 1 Feb. 2019.

“Refinery29 – Company Information.” Meet Refinery29, https://corporate.r29.com/. Accessed 2 Feb. 2019.

Steiner, Linda. “Feminist Media.” The International Encyclopedia of Communication, edited by Wolfgang Donsbach, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2015, pp. 1–6. Crossref, doi:10.1002/9781405186407.wbiecf021.pub2.

Words Of Women Creator on The Collective Power of Female Voices — Beyond The Interview. https://www.beyondtheinterview.com/article/2017/11/11/lauren-martin-words-of-women-instagram-creator. Accessed 4 Feb. 2019.

Appendix One

Rebel Girls YouTube Channel, ‘If Cinderella were a guy’